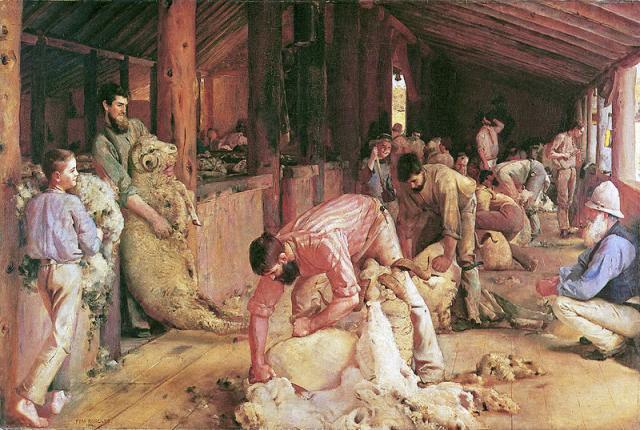

In Tom Roberts’ iconic painting ‘Shearing the Rams’, finished in 1890, a man to the left of the frame hugs a male sheep to his chest, the enormous, heavy creature up to the height of his shoulder.

And next to him, in the foreground, is a shearer bent over another ram, his back straightened and arm outstretched with the force of taking off the animal’s coat – a testament to the complete physicality of the task.

Hailed as a great portrayal of pastoral life, this painting was and is considered a masterpiece of Australian impressionism. It’s also been described as perhaps too nostalgic, as only a year later, newly unionised shearers and squatters would take part in the 1891 Australian shearers strike.

According to the Australian Workers’ Heritage Centre, this strike was a “watershed” in the history of working conditions in this country, and a catalyst in the growth of the Australian Labor Party.

Now, 130 years later, the industry is still facing concerns over conditions, wages and most crucially, attracting young people into their workforce.

Four years ago, it wasn’t as hard for hobby farm owner Catherine Cruikshank to find a shearer to rid her Corriedale sheep of their woolly coats before summer.

The New Gisborne resident said it had become “almost impossible”, and she was paying double compared to three years ago.

“I was actually going to have my sheep transported to another paddock, but I was scared to have them on another property with the cold coming through … that’s when I reached out on social media [and] I finally secured a shearer to get it done,” she said.

“I don’t know if it’s just a dying skill, there’s so much work out there. It’s a real employee’s market, and no one wants to do small packs either.”

Ballarat-based shearer Shane Dunne described a day’s worth of shearing as like “playing four games of AFL in a row”.

He used to work on larger flocks before deciding to concentrate on shearing alpacas and pet sheep on hobby farms, because getting paid as little as $3.80 to $4 a sheep didn’t seem worth it anymore.

Mr Dunne has worked in shearing for two decades, and said to bring more people into the industry, wages will “have to double”.

“Shearing is the hardest physical job on earth – if you’re not going to get paid much, why on earth are you going to do the hardest job in the world,” he said.

He said the work was skilful but unfathomably tiring – “We are expected to drag a 100 kilogram sheep, shear it [while] the animal kicks you for the five minutes it takes to shear it. You get very good at getting your feet right”.

Shearing Contractors Association of Australia secretary Jason Letchford said there were 2800 shearers in the country until 2016, with an extra 500 seasonal workers coming over from New Zealand to get the annual shearing done.

Then the pandemic hit, and not only did those seasonal workers struggle to get into the country, other industries were also looking internally for labour.

“Between 2006 and 2016 we lost 32 per cent of our workforce. That trend of losing 3.2 per cent through the year has been quite consistent,” Mr Letchford explained.

“New workers are coming in, but they are leaving at a faster rate than we can keep them in.”

He said until the drought broke in 2019, the Australian sheep flock numbers had fallen at about the same rate as the number of shearers. But when the rain came, flocks grew again – from about 65 million to about 74 million.

“We haven’t been able to replace the shearers or skilled labour at the same rate as the flock has rebounded,” he said.

Australian Workers Union (AWU) regional and pastoral organiser Ross Kenna said the award rate was too low, about “$3 less than we would like to see” and could be why retention was low.

“Sheds are 150 years old, and [people] are expecting modern shearing to occur in turn of the century sheds,” Mr Kenna said.

“The other big issue is we see a lot of contractors asking for industrial shearers to have their own Australian Business Number – they’ll pay the award but they won’t pay for superannuation and work cover.

“We’re finding shearers who are turning 30 who have no superannuation at all.”

Mr Letchford said the solution to the issue was multifaceted, and broader than pay – it included compensating for the difficulty of the labour with better “manmade conditions” – such as ventilation, accommodation and air conditioning.

While he believed pay could be lucrative, it was the increase in the Australian sheep size which had become too difficult for workers.

“They roughly have gone up 15 kilograms in size, the size of the Australian sheep has gone from being a manageable animal to shear that is almost unmanageable to shear… we need to understand that smaller animals can be more profitable,” he said.

Kilmore shearing trainer, Tom Kelly, described shearing as a “tough industry”, but didn’t believe it was a dying one.

“It’s piecework so you get paid for what you do,” he said.

“And it’s not for everyone, but there’s a lot of people who love it and thrive on it. You have generations of shearing families, the ability to make money quick, the opportunity to travel, the challenge of it.”

But Mr Dunne said it had been a terrible year for wet sheep – the ongoing rains and flooding preventing shearers from working. He wanted to see government farming grants flow on to industries like shearing.

“There’s no such thing as a full-time shearer,” he said.