When describing how the wind changed on the hot, dry night of Ash Wednesday, Mount Macedon firefighter Peter Wuthrich suggests imagining a candle flame, flickering, burning upwards.

“That little tip [at the top], that’s your fire front, blowing north to south, and it’s about one kilometre wide,” he said.

“On Ash Wednesday that candle flame burnt in a southerly direction for 80km.

“But when the south westerly [wind] change came through, you now had 80km to 100km of a firefront … when the wind comes from the other side, that whole height of that candle flame is now your fire front, and it tore [towards Macedon and Mount Macedon].”

Mr Wuthrich is still a firefighter, 40 years on. He fought the fires which ripped through from East Trentham towards Bullengarook before turning to Macedon and Mount Macedon on February 16, 1983.

The inferno killed seven people and destroyed more than 600 buildings.

As the wind changed, the narrow fire which raged through the Wombat State Forest became a wide, wild one, fueled by above 40 degree temperatures, low humidity and years of drought.

“We were in the middle of a drought. We had no reticulated water on Mount Macedon. Water was in short supply. It was the perfect storm, everything was wrong,” Mr Wuthrich said.

He remembers seeing someone who had died trying to escape. One of the hardest things about that night, he said, was trying to fight the hellish blaze in the dark, in choking smoke, showered in cinders.

“On the evening of Ash Wednesday I think we started getting calls about 9pm from people saying they could see flames … we went to investigate where the calls were coming from,” Mr Wuthrich remembered.

The front came so fast and so violently that people were “evacuating as Macedon was exploding”.

“It was basically like incendiaries being dropped on the Macedon township as we drove through,” he said.

Seventy-five people died that day when over 100 fires engulfed parts of Victoria and South Australia – 47 in Victoria and 28 in South Australia – as the blistering heat and flames charged through the bone dry bush.

On that terrible night, Ian Downing witnessed a firestorm roll through his property in Macedon, on Willeys Road.

Then he was caught inside it.

He, his late wife Eve and daughter all bore the scars of fighting – Mr Downing was hospitalised for six weeks with 20 per cent burns to his body from the fire.

Ninety-year-old Mr Downing was once a firefighter too. Two weeks before Ash Wednesday, from February 1, he’d been fighting a fire on the north face of Mount Macedon, where 50 houses were destroyed.

On Ash Wednesday, he was hosing down the back of his home when he saw a spot fire start.

“A big fireball came rolling through the hill. I was standing in this big ball of spark … I just dove into the chook house with my head down … and the radiated heat got me on the hands and my nylon underpants melted across my back,” Mr Downing said.

“It got too hot there, so I ran around behind the water tank and I cut the plastic white pipe up the tank and doused myself with water.

“Then I came inside … my wife had superficial burns on her hands and a bit on her face.

“The daughter had been out looking for the horse. And she came in through the back door and the fly wire door was so hot that the aluminium door melted on her back.”

His daughter, Jeni Emmins, had gone to bed early that night. Then she saw it was raining embers.

“The wind with the fire was just extraordinary, it left the leaves burnt in a horizontal position,” she said.

“Both dad and I forgot gloves, he’d worn the wrong clothing. People think it was the flame but it was the radiated heat.”

Despite having been caught in the flames, Mr Downing feels he “missed out” on efforts to control Ash Wednesday because he had to be taken to hospital so early.

“I had to lay on my guts for a fortnight while they put the skin grafts on. They sew the skin grafts onto your hands, but the one your back [they] just padded it on. I had to lay on my stomach and wait until it settled down,” he said.

Romsey firefighter Ralph Hermann was on the mountain. He said leading up to that day, the air and soil were so parched that the “grass would crackle when you walked on it”.

“There was the anticipation that something was going to happen. The air was just that dry,” Mr Hermann said.

He said devastation was everywhere on the mountain, “you’re driving through flame”.

Fellow Romsey member Ron Cole was fighting a fire out at Tunnel Creek Road in Cherokee earlier in the day, and was patrolling the area when he saw car after car flying towards him.

“I’m thinking, they must have closed the highway, and it was all these people coming off the top of the mountain,” he said.

“They couldn’t get out to the south or the west, so they came over the top.”

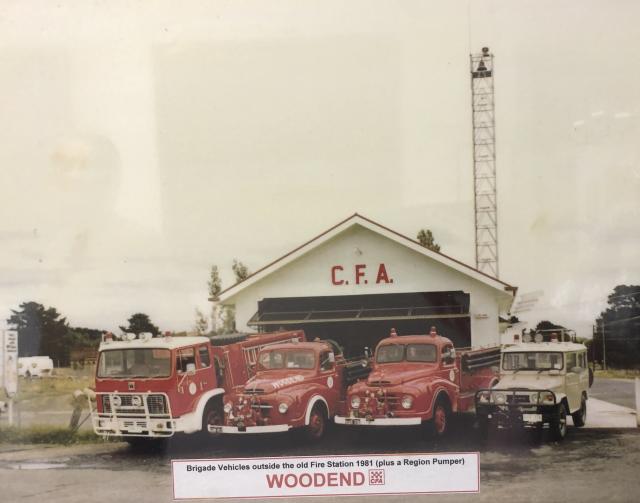

John Keating was first lieutenant of the Woodend Country Fire Authority at the time and said they didn’t have “near the protection” that trucks or personal apparel have today.

Before the wind changed, he received a mayday call from a truck caught in flame in the Wombat State Forest – Woodend CFA firefighter Ray Colban was on the back of it and he’d only been in the brigade for two years.

“[I heard] words to the effect of, ‘mayday, mayday, mayday, we have fire in front of us, fire behind us, we’re going to make a run for it, stand by’,” Mr Keating said.

“That was one of the longest 30 seconds … I have ever experienced, and the relief when [they] radioed back to say … ‘This is RC52, we made it’.”

More than 250 people and their pets took refuge from the inferno inside the old Macedon Railway Hotel, spared while much of the township was destroyed. Hundreds were evacuated from their homes and emergency housing remained on Gisborne Oval for nearly two years.

Mr Downing said many people’s “psychology went” as they tried to get back up and recover. Mr Cole said as with any disaster, it brought the community together.

Reflecting on whether Ash Wednesday lingered in his mind 40 years on, Mr Hermann said if you asked his wife, she’d say yes.

“She would say that after major fires there’s a period I go through, maybe just quietly, she used to say, ‘I know you’ve been affected because you just go quiet for a while’,” he said.